© ~ My Little Old World ~

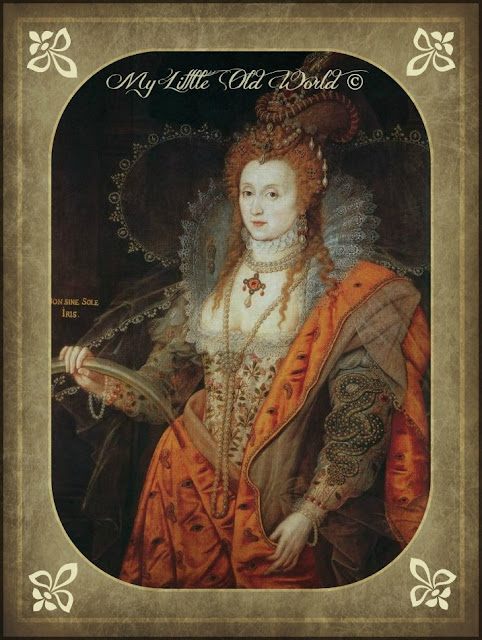

Portrait of Queen Elizabeth I of England (the Armada Portrait), unknown artist, c. 1588, oil on panel,

38 1/2 in. x 28 1/2 in (97.8 mm x 72.4 cm), National Portrait Gallery, London.

(Photo by VCG Wilson/Corbis via Getty Images)

Have you ever wondered why Queen Elizabeth I had adopted such a heavy, immaculate makeup, with lips so red that they made her features hard and severe enough to almost look like a doll, judged excessive even by those who lived at her time, next to her?

Hers was not a simple makeup... it almost looked like 'plaster made of lime' that hardened on the face with the passing of the hours with the consequence of making it almost inexpressive ... and it was a shame because according to the canons of beauty in force at the time when she lived in, she had a pleasant appearance.

One might think that hers was a sort of beauty mask designed to satisfy her desire to keep her skin young by preserving it, with that layer of 'white lead', from all types of atmospheric agents that would have caused it to age, from cold, to the wind, to the sun.

I also came to think that in this way she wanted to distinguish herself from all the other ladies of the Court who also had their faces whitened by powder, but they were less 'ghostly' than he... Maybe this was how she wanted to emphasize her purity, her candor that made her deserve the pseudonym of 'virgin queen'?

In reality, the reasons indicated by the historians were quite different.

Elizabeth I was 29 years old in 1562, exactly 460 years ago, when she was struck by what it was first believed to be a violent fever.

She was ordered by doctors to stay in bed in Hampton Court Palace, but it soon became clear that her illness was more than just a fever: everyone thought that she had contracted smallpox.

This was then a much feared, highly widespread, contagious and deadly viral disease of which thousands of people perished every year.

What began as a trivial disease continued with a rash that then developed into small blisters or pustules that would crack before drying and forming a scab that would leave indelible marks.

During the early stages of smallpox, the queen refused to believe she had been infected with such a terrible disease.

The author Anna Whitelock in The Queen's Bed: An Intimate Story of Elizabeth's Court (2014) writes that Dr. Burcot, a well-known German doctor, was called to her bedside, and that he confirmed that the Queen had been infected with the much feared and terrible illness.

However, as Elizabeth's health deteriorated further, Dr. Burcot was asked for a second consultation following which he confirmed his previous diagnosis.

« It's smallpox » he said to the queen, and Elizabeth groaned and replied:

« The pestilence of God! What is better? To have smallpox on your hands, face or heart that kills your whole body?»

Eventually, the queen became ill to the point to be able to barely speak and after seven days of agony she ended up fearful that she was going to die.

Her ministers then set to work hastily discussing a succession plan and, as the queen had no children, there was great concern as to who would sit on the throne if she would have died suddenly.

The risk that Elizabeth was going to loose her battle against smallpox was very high - about 30 percent of those who contracted the disease died, those who managed to escape the disease wore frightening scars from skin lesions for the rest of their lives.

Elizabeth's most likely heir was Mary, Queen of Scots,

Portrait of Mary Stuart, Queen of Scotland by Anonimus

but because Mary was a Catholic, many British Protestants were concerned about the repercussions of having a Catholic on the throne.

But the question of succession was put aside, as Elizabeth recovered and, although her face was scarred, she was not terribly disfigured.

Different was the fate of her faithful companion, Mary Sidney, who spent hours and hours beside her sick bed, making sure she had plenty of water and tea and was a constant comfort for her: it was not a surprise to find that even she had contracted the dreaded smallpox, the tragedy was that she was severely disfigured throughout her life.

When Elizabeth finally got up from her bed, completely recovered from the disease that almost took her life, she had to think about restoring her beauty to her.

She had always been celebrated for her charm, her elaborate clothes and her flawless white skin, but, after nearly dying from smallpox, the queen carried the memory of her illness throughout her life: she was shocked when she realized that her skin would forever bear the scars of the terrible disease that had struck her.

Probably, for a woman who believed that much of her power was due to her own beauty, it was truly terrible to find herself so changed in her appearance.

She then had to think about covering up the blemishes she now had on her face by using heavy white makeup.

It is known by the name of CERUSE VENEZIANA or BLANC DE CERUSE DE VENISE or even as SPIRITS OF SATURN the mash based on vinegar and white lead with which she used to make her face perfect again, but it was a mixture qualifiable as a potential killer.

Lisa Eldridge writes in her book Face Paint - The story of Makeup (2015) that archaeologists have found traces of white lead in the graves of aristocratic women who already lived in ancient Greek times. It is also believed that the ceruse was used in China during the ancient Shang dynasty (1600-1046 BC).

At the time of Queen Elizabeth I, a woman's totally white face symbolized her youth and fertility and also spoke of her social status, since if a woman had a white face, it was synonymous that she had never had to work outdoors.

Most of women smeared the Venetian ceruse on their face, neck and décolleté. Clearly, the main problem with this 'maquillage' was due to lead and, if used for an extended period of time, it caused illness and / or death.

To make it even worse, white makeup was left on the skin for a long time without being removed: women would leave it on their face for at least a week before cleaning. Those who maintained health and life soon found themselves with gray, wrinkled skin once they removed it.

But the ingredients of the commonly used facial cleanser also had potential lethality: they were used rose water, mercury, honey, and even eggshells. Sure this mixture left the skin soft and smooth, but the mercury had the power to gradually corrode the skin.

To complete her look, the Queen also used bright red pigments on her lips which contained additional heavy metals. It was also fashionable to coat the eyes with black kohl and to use special eye drops based on "belladonna" which dilated the pupils and irritated the eyes making the glance more... languid!

The eyebrows were shaved until they became thin and arched, creating the look of a high forehead that supposedly made women look not only smart but belonging to the upper class. Eventually plants and animal dyes were used for lipsticks.

Elizabeth was very aware of the importance of her appearance in public and, with the clear intention to appear 'regal', she even decided of insisting on having control of her official portraits.

Queen Elizabeth I died at the age of 69, on March 24th, 1603, it was said for an incurable disease. Today, knowing that she lost most of her hair, that she was very fatigued in the last days of her life, that she suffered from memory loss and digestive problems, all symptoms of lead poisoning, the reason for her death is put forward in discussion.

Surely, as she gets older, she will have applied more and more layers of makeup on her face.

And in the light of recent studies, the certainty that the endless attempt to disguise herself in her deadly 'mask of youth' was responsible for her death takes shape today more and more.

Elizabeth I, The Rainbow Portrait (1600) attributed to Marcus Gheeraerts the Younger (1561-1636), collection of the Marquis of Salisbury on display at Hatfield House, Hatfield, Hertfordshire

With utmost gratitude for all the sincere affection and interest you never fail to show me

both with your visits and your beautiful words of appreciation,

I' m sending my dearest love to you

See you soon ❤

SOURCES:

Eldridge Lisa, Face Paint - The story of Makeup (2015)

Whitelock Anna, The Queen's Bed: An Intimate Story of Elizabeth's Court (2014)

La regina Elisabetta I ~ La regina vergine e la sua micidiale maschera della giovinezza

- IMMAGINE 1 -

© ~ My Little Old World ~

Portrait of Queen Elizabeth I of England (the Armada Portrait), unknown artist, c. 1588, oil on panel,

38 1/2 in. x 28 1/2 in (97.8 mm x 72.4 cm), National Portrait Gallery, London.

(Photo by VCG Wilson/Corbis via Getty Images)

Vi siete mai chiesti perché la regina Elisabetta I avesse adottato un 'maquillage' così pesante, immacolato, con labbra così rosse che le rendevano i tratti duri e severi tanto da sembrare quasi una bambola, giudicato eccessivo anche da chi le visse, a suo tempo, accanto?

Il suo non era un semplice trucco... sembrava quasi 'intonaco fatto di calce' che induriva sul volto con il trascorrere delle ore tanto da renderla quasi inespressiva... ed era un peccato perché secondo i canoni della bellezza in vige nell'epoca in cui visse aveva un aspetto gradevole.

Si potrebbe pensare che la sua fosse una sorta di maschera di bellezza studiata per assecondare il suo desiderio di mantenere la pelle giovane preservandola, con quello spesso strato di 'biacca', da ogni tipo di agenti atmosferici che ne avrebbero procurato l'invecchiamento, dal freddo, al vento, al sole.

Sono anche giunta a pensare che così volesse distinguersi da tutte le altre dame di Corte le quali anche avevano il volto imbiancato dalla cipria, ma erano meno 'fantasmatiche' di lei... forse così voleva sottolineare la sua purezza, il suo candore che le fece meritare lo pseudonimo di 'regina vergine'?

In realtà i motivi indicati dagli storici furono ben altri.

Il suo non era un semplice trucco... sembrava quasi 'intonaco fatto di calce' che induriva sul volto con il trascorrere delle ore tanto da renderla quasi inespressiva... ed era un peccato perché secondo i canoni della bellezza in vige nell'epoca in cui visse aveva un aspetto gradevole.

Si potrebbe pensare che la sua fosse una sorta di maschera di bellezza studiata per assecondare il suo desiderio di mantenere la pelle giovane preservandola, con quello spesso strato di 'biacca', da ogni tipo di agenti atmosferici che ne avrebbero procurato l'invecchiamento, dal freddo, al vento, al sole.

Sono anche giunta a pensare che così volesse distinguersi da tutte le altre dame di Corte le quali anche avevano il volto imbiancato dalla cipria, ma erano meno 'fantasmatiche' di lei... forse così voleva sottolineare la sua purezza, il suo candore che le fece meritare lo pseudonimo di 'regina vergine'?

In realtà i motivi indicati dagli storici furono ben altri.

Elisabetta I aveva 29 anni nel 1562, esattamente 460 anni fa, quando fu colpita da quella che si credette essere dapprincipio una febbre violenta.

Le fu ordinato dai medici di rimanere a letto nel suo palazzo di Hampton Court, ma fu presto chiaro che la sua malattia era più che una semplice febbre: si temeva che avesse contratto il vaiolo.

Era questa allora una malattia virale molto temuta, altamente diffusa e contagiosa nonché mortale di cui migliaia di persone perivano ogni anno.

Quella che era iniziata come una banale malattia proseguì con un esantema che poi si sviluppò in piccole vesciche o pustole che si sarebbero spaccate prima di asciugarsi e formare una crosta che avrebbe lasciato segni indelebili.

Durante le prime fasi del vaiolo, la regina si rifiutava di credere di essere stata contagiata da una malattia così terribile.

L'autrice Anna Whitelock in The Queen's Bed: An Intimate Story of Elizabeth's Court (2014) scrive che fu chiamato al suo capezzale un noto medico tedesco, il dottor Burcot, il quale confermò che la regina era stata contagiata dalla tanto temuta e terribile malattia.

Tuttavia, poiché la salute di Elisabetta peggiorò ulteriormente, al dottor Burcot fu chiesto un secondo consulto a seguito del quale egli confermò la sua diagnosi.

« È vaiolo » disse alla regina, ed Elisabetta gemendo replicò:

« La pestilenza di Dio! Cosa è migliore? Avere il vaiolo sulle mani, sul viso o nel cuore che ti uccide tutto il corpo?»

Alla fine, la regina si ammalò al punto da riuscire a malapena a parlare e dopo sette giorni di agonia si finì per temere che stesse per morire.

I suoi ministri si misero quindi al lavoro per discutere frettolosamente un piano di successione e, visto che la regina non aveva figli, c'era grande preoccupazione per chi sarebbe seduto sul trono se Ella fosse morta improvvisamente.

Il rischio che Elisabetta perdesse la sua battaglia contro il vaiolo era molto alto - circa il 30 per cento di coloro che contraevano la malattia morivano, chi riusciva a sfuggire alla malattia portava spaventose cicatrici procurate dalle lesioni cutanee per il resto della sua vita.

Il più probabile erede di Elisabetta era Maria, regina di Scozia,

- IMMAGINE 2 -

Portrait of Mary Stuart, Queen of Scotland by Anonimus

ma poiché Maria era di fede cattolica, molti protestanti britannici erano preoccupati per le ripercussioni che avrebbe potuto procurare l'avere un cattolico sul trono.

Ma la questione della successione fu messa da parte, poiché Elisabetta si riprese e, sebbene il suo viso fosse rimasto sfregiato, non era terribilmente sfigurata.

Diverso fu il destino della sua fedele dama di compagnia, Mary Sidney, che trascorse ore ed ore accanto al letto della sua regina malata, assicurandosi che avesse acqua e tè in abbondanza e rappresentando per lei un conforto costante: non fu una sorpresa scoprire che anch'ella avesse contratto il temuto vaiolo, il dramma fu che ella rimase gravemente deturpata per tutta la vita.

Quando alla fine Elisabetta si alzò dal suo letto, del tutto ripresasi dalla malattia che per poco non le tolse la vita, dovette pensare a ripristinare la sua bellezza.

Ella era da sempre celebrata per il suo fascino, i suoi abiti elaborati e la sua pelle impeccabilmente bianca, ma, dopo aver sfiorato la morte a causa del vaiolo, la regina portò per tutta la vita il ricordo della sua malattia: rimase sconvolta quando si rese conto che la sua pelle avrebbe per sempre portato le cicatrici del terribile morbo che l'aveva colpita.

Probabilmente, per una donna che credeva che gran parte del suo potere fosse dovuto alla propria bellezza, fu davvero terribile scoprirsi così mutata nell'aspetto.

Dovette quindi pensare a coprire le imperfezioni che aveva ora sul viso utilizzando un trucco bianco pesante.

E' conosciuta con il nome di CERUSE VENEZIANA o BLANC DE CERUSE DE VENISE o ancora come SPIRITS OF SATURN la poltiglia a base di aceto e piombo bianco con cui si imbellettava a faceva tornare il suo volto nuovamente perfetto, ma si trattava di un intruglio qualificabile come un potenziale assassino.

L'autrice Lisa Eldridge scrive nel suo libro Face Paint - The story of Makeup (2015) che gli archeologi hanno trovato tracce di piombo bianco nelle tombe di donne aristocratiche che vivevano già ai tempi dell'antica Grecia. Si ritiene inoltre che il ceruse fosse usato in Cina durante l'antica dinastia Shang (1600-1046 a.C.)

Al tempo della regina Elisabetta I, il viso totalmente bianco di una donna ne simboleggiava la giovinezza e la fertilità ed inoltre parlava del suo status sociale, poiché se una donna aveva il volto bianco, era sinonimo del fatto che non aveva mai dovuto lavorare all'aperto.

La maggior parte delle donne si spalmava la ceruse veneziana su viso, collo e décolleté. Chiaramente, il problema principale che questo trucco comportava era dovuto al piombo e, se usato per un periodo di tempo prolungato, causava malattie e / o morte.

A rendere il tutto ancor peggiore, il trucco bianco veniva lasciato sulla pelle per molto tempo senza essere tolto: le donne lo lasciavano sul proprio viso per almeno una settimana prima di pulirsi. Chi conservava la salute e la vita si ritrovava presto con pelle grigia e rugosa una volta che lo aveva rimosso.

Ma anche gli ingredienti del detergente comunemente usato per il viso avevano una potenziale letalità: venivano usati acqua di rose, mercurio, miele e persino gusci d'uovo. Sicuramente questa miscela lasciava la pelle morbida e liscia, ma il mercurio aveva il potere di corrodere a poco a poco la pelle.

Per completare il proprio aspetto la regina utilizzava anche pigmenti rosso vivo sulle labbra che contenevano metalli pesanti aggiuntivi. Era anche di moda rivestire gli occhi con il kohl nero e usare speciali colliri a base di "belladonna" che dilatavano le pupille ed irritavano gli occhi rendendo lo sguardo più... languido!

Le sopracciglia venivano rasate fino a che diventavano sottili e arcuate, creando l'aspetto di una fronte alta che presumibilmente faceva sembrare le donne non solo intelligenti ma della classe superiore. Infine piante e coloranti animali venivano usati per il rossetto.

Elisabetta era molto consapevole dell'importanza del proprio aspetto in pubblico e fece il possibile per apparire 'regale' insistendo per avere il controllo dei suoi ritratti ufficiali.

Elisabetta si spense all'età di 69 anni, il 24 marzo 1603, si diceva per un male inguaribile. Oggi, sapendo che giunse a perdere la maggior parte dei capelli, che era molto affaticata negli ultimi tempi della sua vita, che soffriva di perdita di memoria e problemi digestivi, tutti sintomi questi di avvelenamento da piombo, il motivo della sua morte viene messo in discussione.

Sicuramente, invecchiando, avrà applicati sempre più strati di trucco sul viso.

E alla luce di recenti studi prende sempre più corpo la certezza che sia stato responsabile del suo decesso l'infinito tentativo di travestirsi con la micidiale 'maschera della giovinezza'.

- IMMAGINE 3 -

Elizabeth I, The Rainbow Portrait (1600) attributed to Marcus Gheeraerts the Younger (1561-1636), collection of the Marquis of Salisbury on display at Hatfield House, Hatfield, Hertfordshire

Con la massima gratitudine per l'affetto sincero e l'interesse che non mancate mai di mostrarmi,

sia con le Vostre visite che con le Vostre belle parole di apprezzamento,

Vi invio tanto bene da qui

A presto ❤

FONTI BIBLIOGRAFICHE:

Eldridge Lisa, Face Paint - The story of Makeup (2015)

Whitelock Anna, The Queen's Bed: An Intimate Story of Elizabeth's Court (2014)

LINKING WITH: